|

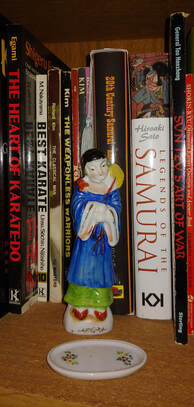

We would visit my grandparents every weekend. My great-grandmother had a bed-sitting room of her own on the main floor. I always enjoyed spending time there with her. She died when I was six years old, and my memories of her are as clear now as when they happened. I distinctly remember that she had a statue of a Japanese woman on a shelf in her room. It was a gift from her brother, Walter, who died during WW1 at Vimy Ridge. He was just a teenager when he died. I knew the statue had a special meaning for her. The statue intrigued me. It was so different from anything I'd ever seen before. Everything about it looked beautiful to me, the woman's style of dress, the colors, and the fan she held in her arms. Being so young, I didn't have much of a vocabulary. Now, the best word to describe what it meant to me was exotic. Looking back on my life, it seems odd that my first connection to Japan and its culture was through my great-grandmother. That connection expanded to encompass most of my life. I've studied several Japanese martial arts, which, in turn, have led me to learn about the history, culture, philosophies, and religions of that country. In the karate dojos where I trained before going to camp, the emphasis had been on physical training, and learning techniques and katas. I enjoyed that very much, and yet, I wanted to learn more. I was looking for the backstory of the martial arts. Access to accurate information about another part of the world was limited back then. I read Black Belt magazine, which was the only one published at the time. It also focused primarily on techniques. The limited information I had access to was from a western perspective because it was filtered through the English language. I wanted, or perhaps needed, to access information about the martial arts from an eastern perspective. The first summer camp I attended was the beginning of a new learning journey. Sensei Richard Kim was the head instructor and founder of the organization. He was a unique martial arts sensei in North America because he was fluent in English and Japanese, so he could easily translate back and forth between the languages. He saw the world from a western and eastern perspective. As a young man, he had lived in Japan for a few years. He trained with some of the best martial arts instructors in Japan and China. And he was a Buddhist priest. As much as I enjoyed the physical training during the day, I looked forward to the lectures at night. The lectures at my first camp included the following topics: * 10 Precepts of Buddhism * Mikkyo (esoteric Buddhism) * Nenriki (mind power, as used by the samurai & later by the ninjas) * Koans (riddles of life, from Zen Buddhism) * The Esoteric Meaning of Katas * Bad Habits & their psychological causes Over the years, I learned that Sensei Kim was teaching us about the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of being human. He was sharing his experiential knowledge with us. Most of what he taught could not be found in books, or now, on the internet. It's been almost twenty years since Sensei passed away. I thought the Japanese influence in my life was complete. A few years ago, my body survived the ravages of prolonged stress brought on by dementia caregiver burnout. Ten months later, just as my body began to heal, my brain broke. Prolonged stress also led to severe cognitive losses and some altered brain functions. My doctor and I discussed the brain's plasticity which allows for the creation of new neural pathways. To bring this about, my doctor prescribed a treatment plan that involved thirty minutes of continuous cardiovascular activity. Within two hours of completing that, I was to do two different brain training activities. I chose Sudoku puzzles and learning the Japanese language. I was to do it every day and if there was not a noticeable difference in my cognitive functioning within three months, my doctor said he would refer me to a neurologist. Fortunately, the referral was not needed. I gradually improved, with a breakthrough after four months. My full recovery took a year and a half. My interest and fascination with the Far East have felt like a thread moving through my life. It's been there since before I was school-aged. It's still weaving its way through my life, as I continue learning the Japanese language.  Over half a century later, my great-grandmother's statue of the Japanese woman sits on my bookshelf. Note: A special thank you to my student, Lyndsay Dobson, for catching my error. Vimy Ridge was during the first world war, not the second. Lyndsay is one of the best proofreaders I know. © Debra J. Bilton. All rights reserved.

1 Comment

After I finished my studies at the University of Guelph in April, I started training at a karate dojo in Hamilton. Imagine my surprise when the sensei informed the class that the organization we belonged to had an annual, week-long martial arts camp at the University of Guelph. What? Why had I not heard of this during the four years that I attended the university?

The sensei at the university never mentioned it in class. Then again, other than a core group of a few students who lived locally, most of the class was made up of university students. They would come and go. Some would stay for a couple of semesters, but most didn't. Perhaps he didn't think anyone would have been interested. The idea of living on campus for a week, with a group of fellow martial artists, intrigued me. It would be new and different. I was all in. After class, I told Sensei that I would like to attend the camp. He gave me an application form, which I took home to fill out and brought back to the next class. Two months after I was done with school, I was back on campus. I had only lived in residence for my last semester at university because I was working on my thesis. I spent a lot of time at the library, so staying on campus saved me time. After registering for the camp, I went to my dorm room to unpack, grabbed a bite to eat, and then went to the lecture hall. Being there felt familiar and odd. It felt familiar because I had sat in that hall for a semester for each of two different courses. It felt odd because I didn't know most of the people there. I knew a few of the people from our dojo, and my sensei from university was there. The majority were strangers to me. Sensei Kim and his assistant, Mr. Leong, came from California. There were people from dojos across Canada, from Massachusetts and Michigan. Little did I know, some of these 'strangers' would be a part of my life for decades to come. And some would become good friends. The first night, we wrote down the schedule for the week to come. Karate and Kobudo (weapons) training after breakfast and in the afternoon. Lectures for the next three evenings, followed by a banquet on the last night. The last morning was the black belt grading, which took place after breakfast. It sounded like it was going to be a great week, except for the part about getting up early for the next five days to do Tai Chi, in a parking lot in front of Johnson Hall, the main residence for the camp. It was to take place from six until seven AM. That would mean getting up between five and five-thirty. Was the sun even up at that time? I would soon find out. Before going to bed the first night, I set my alarm and double-checked it. I didn't want to be late, or worse yet, miss the first class of the camp. I wasn't sure of what to expect. I'd heard of Tai Chi but knew little about it. The impression I had was that it involved moving slowly, and it was for elderly people. There are unspoken rules to any group that you belong to. I quickly learned that you were expected to arrive half an hour before the start time of any class at camp. One morning, I woke before my alarm went off. I thought I'd take advantage of the extra time by going out early to warm up and stretch before the Tai Chi class started. As I opened the large, wooden door to exit Johnson Hall, I expected to see few people in the parking lot. I was stunned to see the entire camp standing facing me, except for Sensei Kim. His back was to me since he was already teaching. It was five-twenty in the morning. I was forty minutes early for class, and I was late. I quickly and quietly walked towards and then around the group, trying to draw as little attention to myself as possible. Sensei Kim turned and looked at me. So much for not drawing attention. After that morning, I always made a point of being in the parking lot before Sensei Kim arrived. It was also a good time to meet people and to get to know some better. Some people would mumble and grumble about having to be up so early, not having had a cup of coffee yet, or breakfast. I had the general impression that the 'karate' people thought that Tai Chi was less important than karate. They showed up every morning and went through the motions because they had to be there. If you missed a class, your sensei wanted to know why. Attendance was considered mandatory. One year, I had a roommate who refused to get up in the morning to go to Tai Chi. I kept encouraging her to come to the class until she abruptly told me that she wanted quality over quantity. After that, I let her sleep. For some reason, her sensei let her get away with it. I wouldn't have dared to try that with my sensei. And besides, I wanted the full camp experience. I also wanted to learn as much as I could in the week I was there. I understand that most people attended the camp for the karate training. That was their main focus. Originally, that my also my main focus. However, I chose to not compare the different martial arts being taught. I didn't see one as better or less than another. Rather, I saw each one as unique and distinct. I've always had to work hard at Karate. It's a challenge for me. Perhaps that's why I like it so much. Tai Chi was different for me, from the start. I learned the moves and then I did it. One movement flowed into the next. It felt natural to me, the way the world is, where everything is connected. Over the years, I've noticed that as some of the karate practitioners have gotten older, they've developed a greater appreciation for Tai Chi. One made a point of saying to me, "I wish I'd paid more attention to the Tai Chi over the years." Also, when you practice Tai Chi regularly, you get better with age, like fine wine. You can't say that about most things in life. Sensei Kim taught many different martial arts. He taught each one with the same level of respect and reverence. He didn't quantify one as better than another. Each was important. It doesn't have to be one or the other. You can study and benefit from Karate and Tai Chi. Doing so helps you to become a more well-rounded martial artist and person. For me, it's the blending of opposites to achieve a balance. Hard and soft, intellect and intuition. One definition of enlightenment is the fusion of intellect and intuition. I clearly remember Sensei Kim saying, "Karate is like cotton wrapped in steel. Tai Chi is like steel wrapped in cotton. They both get you to the same place." © Debra J. Bilton. All rights reserved. |

Debra J. BiltonMartial artist, Sensei, Buddhist. Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed